Friday, August 30, 2024

Drug That Treats Cocaine Addiction May Curb Colon Cancer

Thursday, August 29, 2024

Drug Used to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis May Also Help Prevent It

Thursday, October 6, 2022

Drug turns cancer gene into 'eat me' flag for immune system

The new therapy, described Sept. 12 in Cell Cancer, pulls a mutated version of the protein KRAS to the surface of cancer cells, where the drug-KRAS complex acts as an "eat me" flag. Then, an immunotherapy can coax the immune system to effectively eliminate all cells bearing this flag.

"The immune system already has the potential to recognize mutated KRAS, but it usually can't find it very well. When we put this marker on the protein, it becomes much easier for the immune system," said UCSF chemist and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Kevan Shokat, PhD, who helped lead the new work.

KRAS mutations are found in about one quarter of all tumors, making them one of the most common gene mutations in cancer. Mutated KRAS is also the target of sotorasib, which the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given preliminary approval for use in lung cancer, and the two approaches may eventually work well in combination.

"It's exciting to have a new strategy leveraging the immune system that we can combine with targeted KRAS drugs," said Charles Craik, PhD, a lead study author and professor of pharmaceutical chemistry at UCSF. "We suspect that this could lead to deeper and longer responses for cancer patients."

Turning Cancer Markers Inside Out

The immune system typically recognizes foreign cells because of unusual proteins that jut out of their surfaces. But when it comes to cancer cells, there are few unique proteins found on their outsides. Instead, most proteins that differentiate tumor cells from healthy cells are inside the cells, where the immune system can't detect them.

For many years, KRAS -- despite how common it is in cancers -- was considered undruggable. The mutated version of KRAS, which drives the growth of tumor cells, operates inside cells. It often has only one small change that differentiates it from normal KRAS and doesn't have a readily visible spot on its structure for a drug to bind. But over recent decades, Shokat carried out detailed analyses of the protein and discovered a hidden pocket in mutated KRAS that a drug could block. His work contributed to the development and approval of sotorasib.

Sotorasib, however, doesn't help all patients with KRAS mutations, and some of the tumors it does shrink become resistant and start growing again. Shokat, Craik and their colleagues wondered whether there was another way to target KRAS.

In the new work, the team shows that when ARS1620 -- a targeted KRAS drug similar to sotorasib -- binds to mutated KRAS, it doesn't just block KRAS from effecting tumor growth. It also coaxes the cell to recognize the ARS1620-KRAS complex as a foreign molecule.

"This mutated protein is usually flying under the radar because it's so similar to the healthy protein," says Craik. "But when you attach this drug to it, it gets spotted right away."

That means the cell processes the protein and moves it to its surface, as a signal to the immune system. The KRAS that was once hidden inside is now displayed as an "eat me" flag on the outside of the tumor cells.

A Promising Immunotherapy

With the shift of mutated KRAS from the inside to the outside of cells, the UCSF team was next able to screen a library of billions of human antibodies to identify those that could now recognize this KRAS flag. The researchers showed with studies on both isolated protein and human cells that the most promising antibody they had identified could bind tightly to the drug ARS1620 as well as the ARS1620-KRAS complex.

Then, the group engineered an immunotherapy around that antibody, coaxing the immune system's T cells to recognize the KRAS flag and target cells for destruction. They found that the new immunotherapy could kill tumor cells that had the mutated KRAS and were treated with ARS1620, including those that had already developed resistance to ARS1620.

"What we've shown here is proof of principle that a cell resistant to current drugs can be killed by our strategy," says Shokat.

More work is needed in animals and humans before the treatment could be used clinically.

The researchers say that the new approach could pave the way not only for combination treatments in cancers with KRAS mutations, but also other similar pairings of targeted drugs with immunotherapies.

"This is a platform technology," says Craik. "We'd like to go after other targets that might also move molecules to the cell surface and make them amenable to immunotherapy."

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Drug could be promising new option against eczema

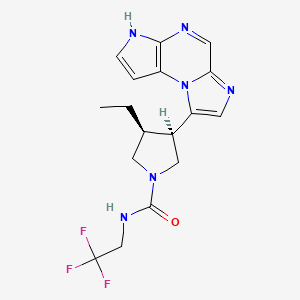

In continuation of my update on Upadacitinib

A pill called upadacitinib, already approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, might also ease another common immunological condition—eczema.

In two phase 3 clinical trials, patients with moderate to severe eczema showed rapid and significant improvements after taking the drug, said researchers at Mount Sinai in New York City.

The clinical trials were funded by the dug's maker, AbbVie Inc., and included nearly 1,700 patients with the inflammatory skin condition.

"The results of these trials ... were so incredible that by week 16, most patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis [eczema] either had a 90% disease clearance, or even 100% disease clearance," study first author Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky said in a Mount Sinai news release. She's professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine, in New York City.

"We achieved extremely high clearance rates that are bringing us closer to the amazing clearance rates that we see in psoriasis," Guttman-Yassky noted.

According to the National Eczema Association, "people with eczema tend to have an over-reactive immune system that when triggered by a substance outside or inside the body, responds by producing inflammation. It is this inflammation that causes the red, itchy and painful skin symptoms common to most types of eczema."

Eczema affects more that 31 million American adults and between 10 to 20% of children, the study authors noted.

The two new clinical trials involved a total of almost 1,700 patients and took place between 2018 and 2020.

Besides the rapid disease clearance noted in patients, "the itch improvements already started to be significant within days from the beginning of the trials, and the maximum clinical efficacy was obtained early, at week 4, and maintained to week 16," Guttman-Yassky said.

The drug was well tolerated by patients who received the two highest doses of the drug—15 milligrams and 30 milligrams—and no significant safety risks were seen, she added.

Upadacitinib is already approved and marketed for use against rheumatoid arthritis under the brand name Rinvoq. It works by blocking what are known as multiple cytokine-signaling pathways—parts of the immune system that can malfunction and cause eczema.

According to Guttman-Yassky, other eczema therapies exist, but most come with certain drawbacks.

While injectable biologic drugs are highly successful in treating eczema patients who don't respond to or can't use topical creams, their use cannot be stopped and restarted at will, because the potential creation of anti-drug antibodies will shorten the half-life of the drugs, she explained.

However, "patients were able to start and restart [upadacitinib] at any time, allowing for flexibility, which cannot be achieved with biologics," Guttman-Yassky, said. "And, biologics, which are injectable agents that target specific lymphocytes that are 'misbehaving' or are up-regulated in atopic dermatitis, do not suppress the entire immune system as other immunosuppressants tend to do."

Dr. Michele Green is a dermatologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City who wasn't involved in the new study.

She called the findings "important."

Upadacitinib is the first drug in its class "to be effectively used for patients with significant improvement of pruritus [itch] within several days of treatment and clearance of their disease within several weeks," Green noted.

"It is also significant since adolescents were included in this study and I believe an oral treatment is much more appealing to treating adolescents than current injectable biologics," she added.

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Upadacitinib#section=2D-Structure

Monday, June 28, 2021

Drug commonly used as antidepressant helps fight cancer in mice

A new study by UCLA researchers suggests that those drugs, commonly known as MAOIs, might have another health benefit: helping the immune system attack cancer. Their findings are reported in two papers, which are published in the journals Science Immunology and Nature Communications.

"MAOIs had not been linked to the immune system's response to cancer before," said Lili Yang, senior author of the study and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. "What's especially exciting is that this is a very well-studied and safe class of drug, so repurposing it for cancer isn't as challenging as developing a completely new drug would be."

Recent advances in understanding how the human immune system naturally seeks out and destroys cancer cells, as well as how tumors try to evade that response, has led to new cancer immunotherapies—drugs that boost the immune system's activity to try to fight cancer.

In an effort to develop new cancer immunotherapies, Yang and her colleagues compared immune cells from melanoma tumors in mice to immune cells from cancer-free animals. Immune cells that had infiltrated tumors had much higher activity of a gene called monoamine oxidase A, or MAOA. MAOA's corresponding protein, called MAO-A, controls levels of serotonin and is targeted by MAOI drugs.

"For a long time, people have theorized about the cross-talk between the nervous system and the immune system and the similarities between the two," said Yang, who is also a UCLA associate professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics and a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. "So it was exciting to find that MAOA was so active in these tumor-infiltrating immune cells."

Next, the researchers studied mice that didn't produce MAO-A protein in immune cells. The scientists found that those mice were better at controlling the growth of melanoma and colon tumors. They also found that normal mice became more capable of fighting those cancers when treated with MAOIs.

Digging in to the effects of MAO-A on the immune system, the researchers discovered that T cells—the immune cells that target cancer cells for destruction—produce MAO-A when they recognize tumors, which diminishes their ability to fight cancer.

That discovery places MAO-A among a growing list of molecules known as immune checkpoints, which are molecules produced as part of a normal immune response to prevent T cells from overreacting or attacking healthy tissue in the body. Cancer has been known to exploit the activity of other previously identified immune checkpoints to evade attack by the immune system.

In the Science Immunology paper, the scientists report that MAOIs help block the function of MAO-A, which helps T cells overcome the immune checkpoint and more effectively fight the cancer.

But the drugs also have a second role in the immune system, Yang found. Rogue immune cells known as tumor-associated macrophages often help tumors evade the immune system by preventing anti-tumor cells including T cells from mounting an effective attack. High levels of those immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages in a tumor have been associated with poorer prognoses for people with some types of cancer.

But the researchers discovered that MAOIs block immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages, effectively breaking down one line of defense that tumors have against the human immune system. That finding is reported in the Nature Communications paper.

"It turns out that MAOIs seem to both directly help T cells do their job, and stop tumor-associated macrophages from putting the brakes on T cells," Yang said.

Combining MAOIs with existing immunotherapies

Yang said she suspects that MAOIs may work well in concert with a type of cancer immunotherapies called immune checkpoint blockade therapies, most of which work by targeting immune checkpoint molecules on the surface of immune cells. That's because MAOIs work on MAO-A proteins, which are inside cells and function differently from other known immune checkpoint molecules.

Studies in mice showed that any of three existing MAOIs—phenelzine, clorgyline or mocolobemide—either on their own or in combination with a form of immune checkpoint blockade therapy known as PD-1 blockers, could stop or slow the growth of colon cancer and melanoma.

Although they haven't tested the drugs in humans, the researchers analyzed clinical data from people with melanoma, colon, lung, cervical and pancreatic cancer; they found that people with higher levels of MAOA gene expression in their tumors had, on average, shorter survival times. That suggests that targeting MAOA with MAOIs could potentially help treat a broad range of cancers.

Yang and her collaborators are already planning additional studies to test the effectiveness of MAOIs in boosting human immune cells' response to various cancers.

Yang said MAOIs could potentially act on both the brain and immune cells in patients with cancer, who are up to four times as likely as the general population to experience depression.

"We suspect that repurposing MAOIs for cancer immunotherapy may provide patients with dual antidepressant and antitumor benefits," she said.

The experimental combination therapy in the study was used in preclinical tests only and has not been studied in humans or approved by the Food and Drug Administration as safe and effective for use in humans. The newly identified therapeutic strategy is covered by a patent application filed by the UCLA Technology Development Group on behalf of the Regents of the University of California, with Yang, Xi Wang and Yu-Chen Wang as co-inventors.

Tuesday, January 12, 2021

Drug eases recovery for those with severe alcohol withdrawal

A drug once used to treat high blood pressure can help alcoholics with withdrawal symptoms reduce or eliminate their drinking, Yale University researchers report Nov. 19 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

In continuation of my update on prazosin

In a double-blind study, researchers gave the drug prazosin or a placebo to 100 people entering outpatient treatment after being diagnosed with alcohol use disorder. All of the patients had experienced varying degrees of withdrawal symptoms prior to entering treatment.

"There has been no treatment readily available for people who experience severe withdrawal symptoms and these are the people at highest risk of relapse and are most likely to end up in hospital emergency rooms," said corresponding author Rajita Sinha, the Foundations Fund Professor of Psychiatry, a professor of neuroscience, and director of the Yale Stress Center.

Prazosin was originally developed to treat high blood pressure and is still used to treat prostate problems in men, among other conditions. Previous studies conducted at Yale have shown that the drug works on stress centers in the brain and helps to improve working memory and curb anxiety and craving.

Sinha's lab has shown that stress centers of the brain are severely disrupted early in recovery, especially for those with withdrawal symptoms and high cravings, but that the disruption decreases the longer the person maintains sobriety. Prazosin could help bridge that gap by moderating cravings and withdrawal symptoms earlier in recovery and increasing the chances that patients refrain from drinking, she said.

One drawback is that in its current form prazosin needs to be administered three times daily to be effective, Sinha noted.

The study was conducted at the Yale Stress Center and the Connecticut Mental Health Center's Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit. It was supported by the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse at the National Institutes of Health and the Connecticut State Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Common Diabetes Drug Invokana (canagliflozin) May Also Shield Kidneys, Heart

A common diabetes drug may also greatly reduce the odds for death from kidney failure and heart disease in diabetes patients with kidney disease, a new study finds.

"Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide, but for almost two decades there have been no new treatments to protect kidney function," noted study lead author Vlado Perkovic. He's a professor at The George Institute for Global Health at Oxford University in the United Kingdom.

"This definitive trial result is a major medical breakthrough as people with diabetes and kidney disease are at extremely high risk of kidney failure, heart attack, stroke and death," Perkovic said in a university news release. "We now have a very effective way to reduce this risk using a once-daily pill."

"Upwards of 40% of end-stage renal disease patients have diabetes as the cause of their renal failure," noted Dr. Maria DeVita, chief of nephrology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City.

"With another impressive study of this family of medications, SGLT2 inhibitors should now be utilized in all type 2 diabetic patients with kidney disease and increased cardiovascular risk," as long as there are no reasons not to do so, Mintz believes.

https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB08907

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canagliflozin

Common Diabetes Drug Invokana (canagliflozin) May Also Shield Kidneys, Heart