An experimental drug for sickle cell disease reduced anemia and boosted the health of red blood cells in patients, according to a new study.

Whether the drug, voxelotor, will have long-term health benefits to patients remains to be seen.

But if approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, "people living with sickle cell disease might have a new, once daily, tolerable oral medication that increases their hemoglobin level in the near future," noted Dr. Banu Aygun, who wasn't involved in the new trial.

She is associate chief of hematology at Cohen Children's Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y.

As Aygun explained, sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder affecting more than 100,000 Americans. Black Americans, especially, are prone to the illness.

"The disease is the result of a change in a single gene leading to the production of an abnormal hemoglobin called sickle hemoglobin [HbS]," Aygun said.

"Due to this abnormal hemoglobin, red blood cells take the shape of a sickle and die much sooner than normal red blood cells. The sickle cells block small blood vessels, causing pain and affecting many organs throughout the body, leading to premature death," she said.

Right now, patients with sickle cell -- many of them children -- have few treatment options. "So far, there are only two FDA-approved drugs for sickle cell disease: hydroxyurea and glutamine," Aygun noted.

The new 17-month, phase 3 clinical trial was designed to see if a third treatment might be on the horizon. It was funded by voxelotor's maker, Global Blood Therapeutics, and included 274 patients, ages 12 to 65, in 12 countries.

Patients were divided into three groups that received either a 900-mg or 1,500-mg daily dose of the drug voxelotor, or a "dummy" placebo pill.

The study found that 51% of patients who took the higher dose of voxelotor had a significant increase in their hemoglobin levels after six months of treatment, compared with 7% of those who received the placebo.

Another finding was that 41% of patients who took the higher dose of the drug reached hemoglobin levels of more than 10g/dl at 24 weeks. A normal, non-anemic hemoglobin count ranges between 11.5 to 17.5 g/dl, depending on age and gender, the study authors noted.

"Chronic organ failure, which is predicted by the severity of anemia, is a leading cause of death for patients with sickle cell disease," said study lead researcher Dr. Elliott Vichinsky, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

"These patients are susceptible to strokes, renal failure and other complications that lead to early death," he said in a UCSF news release. "We believe this drug has the potential to decrease chronic organ failure in patients with this condition."

For her part, Aygun said the new drug does seem to hold promise, but gains for patients were so far not dramatic.

She noted that patient pain "events" didn't change, regardless of whether people received voxelotor or the placebo. The most common side effects with the new drug were headache and diarrhea.

And Aygun stressed that it remains to be seen "whether taking this medication for longer duration will lead to a decrease in pain events or organ damage caused by sickle cell disease."

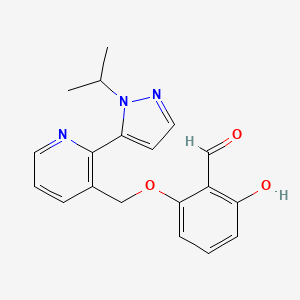

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Voxelotor#section=2D-Structure

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voxelotor