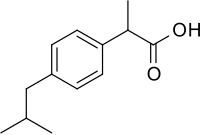

In continuation of my update on Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen: You can buy it at any drug store, and it will help with that stabbing headache or sprained ankle. One of the ways it does so is by reducing inflammation, and it is this property that may also help patients with cystic fibrosis.

Research has found that ibuprofen, when taken at high doses, helps slow the progression of lung function decline in people with cystic fibrosis, a disease caused by having two 'bad' copies of a gene that codes for a protein important in fluid secretion. Improved lung function is important, given that most people diagnosed die by their early 50s, usually due to chronic lung infections caused by their inability to move particles, including bacteria, up and out of the lungs. The downside is that ibuprofen doses that high, when taken routinely, can result in gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and—when combined with the antibiotics that these patients often have to take for their recurring lung infections—acute kidney injury.

But what if you could get the drug just to the area that needs it: the lungs? You could harness ibuprofen's benefits without the negative side effects.

Carolyn Cannon, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine, is working on a way to do just that.

"We feel that nanoparticle ibuprofen delivered by aerosol to the lungs would be a fantastic therapeutic," Cannon said. And because it is essentially a repurposed drug—only the delivery method is different—the development and regulatory approval process should be relatively easy, in comparison to the requirements for a novel therapeutic.

"The researchers who performed the original ibuprofen study thought it was working solely by inhibiting the migration of a type of white blood cell, called the neutrophil, to the lung. It goes hand-in-hand with acute inflammation," Cannon said. "However, although this may be one mechanism of action, at the high doses that were being given to the cystic fibrosis patients, the drug also has antimicrobial properties."

The inhaled ibuprofen would work in conjunction with the antibiotics the patient is already being given for the underlying infection. "We determined that not only does ibuprofen act as an antimicrobial itself, it is also synergistic with the antibiotics we already give to these patients," Cannon said.

"Together, they kill the pathogens much better than either one does alone and we could get the same great effects of the high concentrations of ibuprofen without the side effects."

Cannon and her team are pursuing international patent protection on this technology and, in the next year or so, hope to begin discussions with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about working towards receiving Investigational New Drug (IND) status to allow for future clinical trials.

"We have several nanoparticle formulations, one of which, developed by our collaborator, Dr. Hugh Smyth at the University of Texas in Austin, is almost pure ibuprofen," Cannon said. "We are excited about this formulation, but we still have to prove that it achieves our goal of high lung concentrations of the drug and low systemic concentrations."

To test this, this summer Cannon and Smyth and their teams plan to deliver the ibuprofen nanoparticles to the lungs of animal models and measure the drug concentrations in the lungs and serum at different time points. "This type of experiment addresses the pharmacokinetics of the drug and aims to investigate our hypothesis that we can achieve high local concentrations in the lung while maintaining low systemic concentrations," Cannon said. She and her collaborators will also investigate the capacity of the ibuprofen nanoparticles to improve pneumonia survival rates in animal models.

"The staff in the Office of Technology Translation at the Health Science Center have been wonderful through the whole process," Cannon said. "They have served as advocates for our projects with the Texas A&M Technology Commercialization (TTC) team, which has helped actualize our vision to move our inventions from the lab into use by patients."

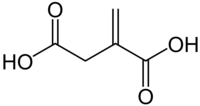

Itaconic acid

Itaconic acid