Saturday, August 27, 2016

Friday, August 26, 2016

Existing non-antibiotic therapeutic drugs could help combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens

The rise of antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens is an increasingly global threat to public health. In the United States alone antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens kill thousands every year.

But non-antibiotic therapeutic drugs already approved for other purposes in people could be effective in fighting the antibiotic-resistant pathogens, according to a new study from researchers at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Antibiotic resistance is increasing due to the over prescription of antibiotics, said Ashok Chopra, a professor at UTMB and author of the new study in the Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. But the solution could lie with drugs originally meant for other uses that, until now, no one knew could also help combat bacterial infections.

While antibiotics have been highly effective at treating infectious diseases, infectious bacteria have adapted to them and antibiotics have become less effective, according to the Centers for disease Control and Prevention. About 2 million people in the United States are infected with antibiotic resistant bacteria every year and at least 23,000 die, according to the CDC.

"There are no new antibiotics which are being developed and nobody really has given much emphasis to this because everyone feels we have enough antibiotics in the market," Chopra said. "But now the problem is that bugs are becoming resistant to multiple antibiotics. That's why we started thinking about looking at other molecules that could have some effect in killing such antibiotic resistant bacteria."

By screening a library of 780 Food and Drug Administration approved therapeutics, Chopra, Jourdan Andersson, a graduate student at UTMB, and others on the research team were able to identify as many as 94 drugs that were significantly effective in a cell-culture system when tested against Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that cause the plague and which is becoming antibiotic resistant.

After further screening, three drugs, trifluoperazine, an antipsychotic, doxapram, a breathing stimulant, and amoxapine, an anti-depressant, were used in a mouse model and were found to be effective in treating plague. In further experiments, trifluoperazine was successfully used to treat Salmonella enterica and Clostridium difficile infections, both of which are listed as drug-resistant bacteria of serious threat by the CDC.

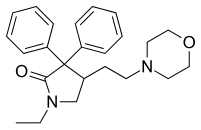

Amoxapine

Amoxapine  Doxapram hydrochloride

Doxapram hydrochloride Trifluoperazine

Trifluoperazine

"It is quite possible these drugs are already, unknowingly, treating infections when prescribed for other reasons," Chopra said.

Since these are not antibiotics these drugs are not attacking the bacteria. Instead, they could be dealing with these bacteria in a couple of different ways, Chopra said.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

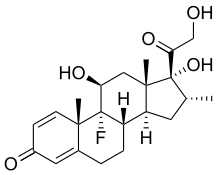

One-dose of dexamethasone can improve outcomes of asthmatic patients in ER

In continuation of my update on dexamethasone

Adults with asthma who were treated with one-dose dexamethasone in the emergency department had only slightly higher relapse than patients who were treated with a 5-day course of prednisone. "Enhanced compliance and convenience may support the use of dexamethasone" is the conclusion of a study that was published online Friday inAnnals of Emergency Medicine ("A Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial of Single Dose vs. Five Days of Oral Dexamethasone in Acute Adult Asthma").

"Any time we can reduce the role of patient compliance with asthma, we have a chance of improving outcomes," said lead study author Matthew W. Rehrer, MD, of the Department of Emergency Medicine with Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif. "Dexamethasone allows the emergency physician to administer treatment in one dose and doesn't rely on the patient to remember to take her pills for four more days after leaving the ER. A single dose of medication eliminates prescription adherence barriers such as forgetfulness, cost and dose omission."

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

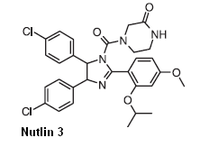

Experimental drug cancels effect from key intellectual disability gene in mice.

A University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher who studies the most common genetic intellectual disability has used an experimental drug to reverse -- in mice -- damage from the mutation that causes the syndrome.

The condition, called fragile X, has devastating effects on intellectual abilities.

Fragile X affects one boy in 4,000 and one girl in 7,000. It is caused by a mutation in a gene that fails to make the protein FMRP. In 2011, Xinyu Zhao, a professor of neuroscience, showed that deleting the gene that makes FMRP in a region of the brain that is essential to memory formation caused memory deficits in mice that mirror human fragile X.

The deletions specifically affected neural stem cells and the new neurons that they form in the hippocampus.

Tantalizingly, Zhao's 2011 study showed that reactivating production of FMRP in new neurons could restore the formation of new memories in the mice. But what remained unclear was exactly how the absence of FMRP was blocking neuron formation, and whether there was any practical way to avert the resulting disability.

Now, in a study published on April 27 in Science Translational Medicine, Zhao and her colleagues at the Waisman Center at UW-Madison have detailed new steps in the complex chain reaction that starts with the loss of FMRP and ends up with mice that cannot remember what they had recently been sniffing.

This study's newfound understanding of the biochemical chain of events became the basis for identifying an experimental cancer drug called Nutlin-3, which blocks the reaction.

In the new study, mice with the FMRP deletion took Nutlin-3 for two weeks. When tested four weeks later, they regained the ability to remember what they had seen -- and smelled -- in their first visit to a test chamber.

Statistically, the memory capacities of normal mice and fragile X models that were treated with Nutlin-3 were identical.

Still, many hurdles remain before the advance can be tested on human patients, Zhao says. "We are a long way from declaring a cure for fragile X, but these results are promising."

Fragile X appears after birth, says Zhao. "Parents start to notice something is wrong, but even if they get an accurate diagnosis, there is no treatment at present. I'm encouraged because affecting this gene's pathway does seem to reverse the memory impairment."

The mouse memory test relied on curiosity. "We placed two objects in an enclosure and let the mice run around," Zhao says. "Mice are naturally curious, so they explore and sniff each one. We take them out after 10 minutes, replace one object with a different one, wait 24 hours and put the mouse back in. If the mouse has normal learning ability, it will recognize the new object and spend more time with it. Mice without the FMRP gene don't remember the old object, so they spend a similar amount of time on each one."

The behavioral assessment was done by different people, says Zhao. "First author Yue Li, a postdoctoral researcher at Waisman, ran the test and sent the video to Michael Stockton, an undergraduate working on the project." Stockton timed how and where each mouse was exploring, "but he had no idea which mouse was which," Zhao says. "It was fantastic to see such clear data."

Two other undergraduates, Jessica Miller and Ismat Bhuiyan (who is now in graduate school) and postdoctoral fellows Brian Eisinger and Yu Gao also worked on the study. The Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation has applied for a patent on the discovery.

Nutlin-3, which can block the last stage of the chain reaction set off by a mutation in the FMRP gene, is in phase 1 trial for the treatment of the eye cancer retinoblastoma. Finding a new use for a drug that is approved, or that like Nutlin-3 and several derivatives, has entered the approval process, may shorten the lengthy FDA process, says Zhao.

The dose used in the trial -- only 10 percent of the dose proposed for cancer chemotherapy -- caused no apparent harm, she says. "We measured body weight and activity. So far, the mice look healthy and happy."

Because more than one-third of fragile X patients are also diagnosed with autism, the study may shed light on that condition.

In any case, it's far too soon to declare victory over fragile X, Zhao stresses. "There are many hurdles. Among the many questions that need to be answered is how often the treatment would be needed. Still, we've drawn back the curtain on fragile X a bit, and that makes me optimistic."

Monday, August 22, 2016

New molecule-building method may have great impact on pharmaceutical industry

Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have devised a new molecule-building method that is likely to have a major impact on the pharmaceutical industry and many other chemistry-based enterprises.

The method, published as an online First Release paper in Science on April 21, 2016, allows chemists to construct novel, complex and potentially very valuable molecules, starting from a large class of compounds known as carboxylic acids, which are relatively cheap and non-toxic. Carboxylic acids include the amino acids that make proteins, fatty acids found in animals and plants, citric acid, acetic acid (vinegar) and many other substances that are already produced in industrial quantities.

"This is one of the most useful methods we have ever worked with, and it mostly involves materials that every chemist has access to already, so I think the interest in it will expand rapidly," said principal investigator Phil S. Baran, Darlene Shiley Professor of Chemistry at TSRI.

"This exciting new discovery represents a significant advance in our ability to transform simple organic molecules and to rapidly build complex structures from readily available materials—we expect to use it in both the discovery and development of biologically active compounds that help patients prevail over serious disease," said co-author Martin D. Eastgate, a Director in Chemical and Synthetic Development at Bristol-Myers Squibb, who participated in the study as part of a long-standing research collaboration between Bristol-Myers Squibb and TSRI.

The new method is a modification of what is already one of the most widely used sets of chemical reactions: amide bond-forming reactions. These occur naturally in cells to stitch together amino-acids into proteins, for example. Since the 1940s, when they became a popular tool for laboratory chemists, they have been instrumental in the discovery of many new compounds as well as new methods for synthesizing compounds.

Amide bond-forming reactions couple carbon atoms on carboxylic acids to nitrogen atoms on another broad class of compounds called amines. The reactions are relatively safe and easy, and produce water, H2O, as a co-product. Chemists have long dreamed of using similarly cheap and easy techniques to make carbon-to-carbon couplings. That would enable them to synthesize, and potentially turn into drugs and other useful products, an enormous number of organic molecules that have previously been inaccessible.

Carbon to Carbon

The method devised by Baran and his team essentially repurposes the traditional amide bond-forming strategy to achieve carbon-carbon couplings. The new reactions again involve easy, safe conditions—the co-product now is carbon dioxide, CO2—and the same inexpensive and widely available starting materials, carboxylic acids. This time the reaction partners are not nitrogen-containing amines but organic compounds containing carbon and zinc, which are also relatively easy to buy or make.

The path to the new invention began with a long-known reaction called the Barton decarboxylation. "We started by asking ourselves what would happen if we could use a metal to trap a radical [a highly reactive charged molecule] generated in the Barton decarboxylation," said TSRI Research Associate Josep Cornella. "We realized that if we could do that, it would open up a totally new approach to organic synthesis and carbon-carbon coupling."

The method the team ultimately developed employs an inexpensive and commercially available activating agent that primes the chosen carboxylic acid for the reaction. A metal catalyst—inexpensive nickel—then facilitates the reaction between the carboxylic acid and its carbon-zinc partner compound.

A key ingredient turned out to be a "ligand" compound that helps the metal catalyst do its job. "We found that common, readily available bipyridine ligands work best—these help to stabilize the nickel so it can catalyze the reaction," said TSRI Research Associate Tian Qin.

Friday, August 19, 2016

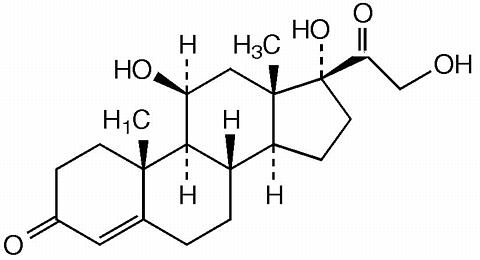

Hydrocortisone drug can also prevent lung damage in premature babies

Research from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago conducted in mice shows the drug hydrocortisone a steroid commonly used to treat a variety of inflammatory and allergic conditions -- can also prevent lung damage that often develops in premature babies treated with oxygen.

If affirmed in human studies, the results could help pave the way to a much-needed therapy for a bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a condition that affects 10,000 newborns in the United States each year and can lead to chronic lung disease and, ultimately, heart failure. In a set of experiments, to be published in the May print issue of the journal Pediatric Research, a team of Lurie Children's scientists showed the drug reduced damage to the delicate blood vessels inside the lungs of newborn mice and reversed some of BPD's harmful downstream effects on the heart.

"Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is a devastating, often unavoidable side effect of a standard lifesaving therapy with oxygen used to treat newborn babies, so our findings are a promising indicator that a well-known drug that's been around for a long time may help stave off some of this condition's worst after-effects," says study lead investigator and Lurie Children's neonatologist Marta Perez, M.D., who is also assistant professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Soy shows promise as natural anti-microbial agent

In continuation of my update on soy

Soy isoflavones and peptides may inhibit the growth of microbial pathogens that cause food-borne illnesses, according to a new study from University of Guelph researchers.

Soybean derivatives are already a mainstay in food products, such as cooking oils, cheeses, ice cream, margarine, food spreads, canned foods and baked goods.

The use of soy isoflavones and peptides to reduce microbial contamination could benefit the food industry, which currently uses synthetic additives to protect foods, says engineering professor Suresh Neethirajan, director of the BioNano Laboratory.

U of G researchers used microfluidics and high-throughput screening to run millions of tests in a short period.

They found that soy can be a more effective antimicrobial agent than the current roster of synthetic chemicals.

The study is set to be published in the journal Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports this summer and is available online now.

"Heavy use of chemical antimicrobial agents has caused some strains of bacteria to become very resistant to them, rendering them ineffective for the most part," said Neethirajan.

"Soy peptides and isoflavones are biodegradable, environmentally friendly and non-toxic. The demand for new ways to combat microbes is huge, and our study suggests soy-based isoflavones and peptides could be part of the solution."

Neethirajan and his team found soy peptides and isoflavones limited growth of some bacteria, including Listeria and Pseudomonas pathogens.

"The really exciting thing about this study is that it shows promise in overcoming the issue of current antibiotics killing bacteria indiscriminately, whether they are pathogenic or beneficial. You need beneficial bacteria in your intestines to be able to properly process food," he said.

Peptides are part of proteins, and can act as hormones, hormone producers or neurotransmitters. Isoflavones act as hormones and control much of the biological activity on the cellular level.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

New drug combination before surgery may improve outcomes in breast cancer patients

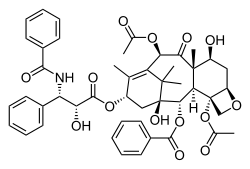

In continuation of my update on Paclitaxel

Results from the I-SPY 2 trial show that giving patients with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer a combination of the drugs trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab before surgery was more beneficial than the combination of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. Previous studies have shown that a combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab is safe and effective against advanced, metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, but in the new results, investigators tested whether the combination would also be effective if given earlier in the course of treatment. Results of the study are presented by trial investigators from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania at the AACR Annual Meeting 2016, April 16-20.

In this latest phase of the I-SPY2 trial, investigators worked to determine whether T-DM1 plus pertuzumab could eradicate residual disease (known as pathological complete response, or pCR) for more patients if delivered before surgery to shrink cancer tumors compared with paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. They also examined whether this combination could meet that goal without the need for patients to receive paclitaxel.

"The combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab substantially reduced the amount of residual disease in the breast tissue and lymph nodes for all subgroups of HER2-positive breast cancers compared with those in the control group," said lead author, Angela DeMichele, MD, MSCE, a professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who will present the findings. "Our results suggest a possible new treatment option for patients that can not only effectively shrink tumors in the breast, but potentially reduce the chance of the cancer coming back later. The results also show that by replacing older, non-targeted therapies with more effective and less-toxic new therapies, we have the potential to both improve outcomes and decrease side effects."

For the study, patients whose tumors were 2.5 cm or bigger were randomly assigned to 12 weekly cycles of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab (control) or T-DM1 plus pertuzumab (test). Following the initial test period, all patients received four cycles of the chemotherapies doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, and surgery. Patients' tumors were then tested for one of three biomarker signatures: HER2-positive, HER2-positive and hormone receptor (HR)-positive, and HER2-positive and HR-negative.

New drug combination before surgery may improve outcomes in breast cancer patients: Results from the I-SPY 2 trial show that giving patients with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer a combination of the drugs trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab before surgery was more beneficial than the combination of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab.

Labels:

HER2-positive,

paclitaxel,

Pertuzumab

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

New clinical study to evaluate inexpensive drug to prevent type 1 diabetes

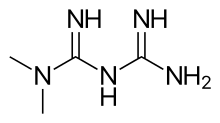

In continuation of my update on metformin

New trial aims to prevent type 1 diabetes

A clinical study evaluating a new hypothesis that an inexpensive drug with a simple treatment regimen can prevent type 1 diabetes will be launched in Dundee tomorrow.

The autoimmune diabetes Accelerator Prevention Trial (adAPT) is led by Professor Terence Wilkin, of the University of Exeter Medical School, with support from colleagues at the University of Dundee and NHS Tayside. It will be launched at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, on Tuesday, 19th April.

Initial funding of $1.7 million is being provided by JDRF, the leading global organisation backing type 1 diabetes research. The study aims to contact all 6,400 families in Scotland affected by the condition, with a view to expanding into England at a later date. Children aged 5 to 16 who have a sibling or parent with type 1 diabetes will be invited for a blood test to establish whether they are at high risk of developing the disease. If so, they will be invited to take part in the trial.

Researchers will then examine the impact of administering metformin, the world's most commonly prescribed diabetes medicine, to young people in the high-risk category. If successful, the large-scale trial could explain why the incidence of type 1 diabetes has risen five-fold in the last 40 years, and provide a means of preventing it.

Researchers have previously hypothesised that type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease caused by a faulty immune system which attacks and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Clinical trials have tried drugs that supress the immune system to attempt to subdue the attack, but the results have so far been disappointing.

The Accelerator Prevention Trial is the first to test an alternative explanation for type 1 diabetes, and is based on the accelerator hypothesis, proposed in 2001 by Professor Wilkin.

This hypothesis theorises that autoimmunity occurs as a response to damaged beta cells. It believes that beta cells, stressed by being made to work too hard in a modern environment, send out signals that switch on the immune system. adAPT will test whether metformin, which is known to protect the beta cells from stress, can stop the immune response that goes on to destroy them.

Professor Wilkin said, "We still have no means of preventing type 1 diabetes, which, at all ages, results from insufficient insulin. We all lose beta cells over the course of our lives, but most of us have enough for normal function.

"However, if the rate of beta cell loss is accelerated, type 1 diabetes develops, and the faster the loss, the younger the onset of the condition. The accelerator hypothesis talks of fast and slow type 1 diabetes - beta cell loss which progresses at different rates in different people, and appears at different ages as a result."

Monday, August 15, 2016

Experimental treatment shrinks rare pediatric tumor by 90%

When a baby's life was threatened by a rare pediatric cancer that would not respond to surgery or chemotherapy, doctors at Nemours Children's Hospital rapidly, successfully shrank the tumor by 90 percent using an experimental treatment, according to a new study published online in Pediatric Blood and Cancer. The now-20-month-old girl achieved the remarkable improvement by receiving a drug called LOXO-101 that was being tested on adults, researchers reported.

"Most infants and children with infantile fibrosarcoma (IFS) can be cured through surgery and chemotherapy. When our patient's disease progressed in spite of these treatments, we had to investigate new options that could target the disease," said Dr. Ramamoorthy Nagasubramanian M.D., lead author of the manuscript, division chief of pediatric hematology-oncology at Nemours Children's Hospital. "The dramatic reduction in tumor size shows early but promising evidence of the potential for LOXO-101 to provide significant benefit for pediatric patients with NTRK gene fusions."

Nemours' oncology team operated on the girl at 6 months to remove a large tumor located in the neck and face. The tumor did not respond to standard chemotherapy and relapsed after extensive surgery. Genetic testing confirmed an ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion, which is frequently found in IFS. At the time, LOXO-101 was in a Phase 1 multi-center basket trial in adults. Working with Nemours, Loxo Oncology, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company developing highly selective medicines for patients with genetically defined cancers, was able to expand the trial to children and enroll her.

Friday, August 12, 2016

Scientists develop new drug for life-threatening lung disease treatment

Researchers are developing a new drug to treat life-threatening lung damage and breathing problems in people with severe infections like pneumonia, those undergoing certain cancer treatments and premature infants with underdeveloped, injury prone lungs.

Scientists at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center report April 19 in Science Signaling that a transcription factor called FOXF1 activates several biological processes that promote recovery from acute lung injury. Two laboratories at Cincinnati Children's are developing a pharmacologic compound that in mouse models stimulates FOXF1 and promotes repair after lung injury.

"Besides toxic insults from some cancer treatments, acute lung injury can be a major medical problem for people who get infectious diseases like flu, pneumonia or Ebola because of pathogens that target the lung," said Vladimir Kalinichenko, MD, PhD, co-senior author and a physician and researcher in the Divisions of Pulmonary Biology and Developmental Biology at Cincinnati Children's. "A small molecule compound we developed efficiently stabilizes the FOXF1 protein in cell cultures and mouse lungs, and it shows promise in inhibiting lung inflammation and protecting experimental mice from lung injury."

Along with co-senior author Tanya Kalin, MD, PhD, in the Cincinnati Children's Perinatal Institute, the research team learned that loss of FOXF1 in lung endothelial cells of mice caused them to die from respiratory problems, pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs) and lung inflammation. This happens when endothelial cells that line blood vessels in the lung can no longer provide a protective barrier between the external environment and the body's circulatory system.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

Frontline nilotinib supported for newly diagnosed CP-CML

Long-term results from the ENESTnd trial indicate a favourable risk-benefit profile for frontline use of nilotinib in patients within 6 months of chronic phase-chronic myeloid leukaemia (CP-CML) diagnosis.

"Throughout the study, nilotinib has demonstrated several benefits over imatinib in surrogate endpoints of therapeutic efficacy, such as higher rates of response and lower rates of disease progression, death due to advanced CML and treatment-emergent BCR-ABL mutations", the researchers report in Leukemia.

"The risk of AEs [adverse events] (regardless of AE type) appears to be similar with nilotinib and imatinib; however, each TKI [tyrosine kinase inhibitor] is associated with different types of AEs, including a higher risk of CVEs [cardiovascular events] with nilotinib vs imatinib."

By 5 years, 77.0% of the 282 patients randomly assigned to receive nilotinib 300 mg twice daily and 77.2% of the 281 using nilotinib 400 mg twice daily achieved a major molecular response (BCR-ABL ≤0.1% on the International Scale [BCR-ABLIS]) compared with 60.4% of the 283 patients given imatinib 400 mg once daily.

Deep molecular responses by 5 years were also more common with nilotinib 300 mg and 400 mg than with imatinib, with rates of MR4 (BCR-ABLIS ≤0.01%) of 65.6%, 63.0% and 41.7%, respectively. The corresponding rates for MR4.5 (BCR-ABLIS ≤0.0032%) were 53.5%, 52.3% and 31.4%.

And estimated 5-year progression-free survival was 92.2%, 95.8% and 91.0% for the nilotinib 300 mg and 400 mg groups and the imatinib group, respectively. Overall survival at 5 years was estimated to be 93.7%, 96.2% and 91.7%, respectively.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Antidepressant Wellbutrin linked to long-term modest weight loss

Group Health researchers have found that bupropion (marketed as Wellbutrin) is the only antidepressant that tends to be linked to long-term modest weight loss.

Previously, Group Health researchers showed a two-way street between depression and body weight: People with depression are more likely to be overweight, and vice versa. These researchers also found that most antidepressant medications have been linked to weight gain.

Prior research on antidepressants and weight change was limited to one year or shorter. But many people take antidepressants--the most commonly prescribed medications in the United States--for longer than a year. So for up to two years the new study followed more than 5,000 Group Health patients who started taking an antidepressant. TheJournal of Clinical Medicine published it: "Long-Term Weight Change after Initiating Second-Generation Antidepressants."

"Our study suggests that bupropion is the best initial choice of antidepressant for the vast majority of Americans who have depression and are overweight or obese," said study leader David Arterburn, MD, MPH. He's a senior investigator at Group Health Research Institute (GHRI), a Group Health physician, and an affiliate associate professor in the University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine's Department of Medicine. But in some cases, an overweight or obese patient has reasons why bupropion is not for them--like a history of seizure disorder--and it would be better for them to choose a different treatment option.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

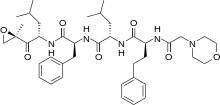

Novel combination of cancer drugs can have therapeutic impact on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

New research from Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) shows that promising cancer drugs used in combination can have significant therapeutic impact on a particularly aggressive subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DH-DLBCL) in preclinical studies. The researchers will present their findings at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2016, to be held April 16-20 in New Orleans.

Priyank Patel, MD, a fellow in the Department of Medicine at Roswell Park, is the first author and Francisco Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, MD, Clinical Chief of the Institute's Lymphoma/Myeloma Service, is the senior author of "Investigating novel targeted therapies for double hit diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DH-DLBCL)" (abstract 3038), which will be presented on Tuesday, April 19, at 8 a.m. CDT.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, is an aggressive form of lymphoma. This research team reviewed a database of 650 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, identifying 36 patients whose tumors had two or more aberrant genes. Patients with mutations of the c-MYC, BCL2 and/or BCL6 genes — a subtype known as "double-hit lymphoma" — have especially have poor outcomes when treated with standard chemotherapy. The scientists evaluated the effectiveness of three novel anticancer drug candidates that targeted those proteins. In preclinical studies, the therapeutic agents ABT-199, JQ-1 and carfilzomib induced cell death in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Significant synergistic activity was observed when researchers combined ABT199 with carfilzomib and, to a lesser extent, with JQ1 in cancer cell lines.

"Increasing knowledge of genetics and molecular pathways has helped us identify a subgroup of patients who harbor aggressive aberrant gene mutations. Understanding the mechanisms of action and clarifying how these potential therapies work to inhibit cancer cell growth may result in improved outcomes for patients diagnosed with this aggressive type of lymphoma," says Dr. Hernandez-Ilizaliturri.

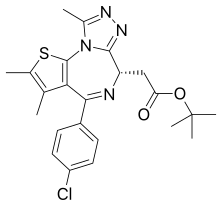

Carfilzomib

Carfilzomib  JQ1

JQ1  ABT-199

ABT-199

Novel combination of cancer drugs can have therapeutic impact on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: New research from Roswell Park Cancer Institute shows that promising cancer drugs used in combination can have significant therapeutic impact on a particularly aggressive subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DH-DLBCL) in preclinical studies. The researchers will present their findings at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2016, to be held April 16-20 in New Orleans.

Monday, August 8, 2016

Potential first-in-class treatment is well-tolerated in patients with chronic hepatitis B: Phase 1 study shows the investigational capsid assembly inhibitor NVR 3-778 combined with pegylated interferon reduces levels of hepatitis B more than NVR 3-778 alone.

New data presented today confirms that a novel first-in-class treatment for Hepatitis B, called NVR 3-778, is well-tolerated and can reduce levels of the virus' genetic material in the body when combined with pegylated interferon after four weeks of treatment. The updated Phase 1b trial results were presented today at The International Liver CongressTM 2016 in Barcelona, Spain.

NVR 3-778 is a first-in-class HBV capsid assembly inhibitor which modulates the function of the core protein. This protein plays an essential role in viral replication and persistence of the virus.

Approximately 14 million people within the World Health Organization European region are chronically infected with Hepatitis B.1 There are several medicines that are effective at suppressing the virus over many years, slowing down damage to the liver, and allowing the body to repair itself.2 However, it is unusual for these treatments to clear the virus permanently.3

"Previous Phase 1 results with NVR 3-778 have shown reduction in HBV viral load," said Dr Man-Fung Yuen of Queen Mary Hospital, University of Hong Kong, and lead author of the study. "It is promising to see that the combination of NVR 3-778 with pegylated interferon produces responses that are greater than those seen with either monotherapy."

The international Phase 1b study was conducted in 64 patients who had not previously received any treatment for Hepatitis B. There were six dosing cohorts in the study: 100mg daily, 200mg daily, 400mg daily, 600mg twice a day, or 600mg twice a day combined with pegylated interferon, and finally pegylated interferon combined with placebo. Treatment was given for a total of 28 days.

The results demonstrated that NVR 3-778 was well tolerated in all cohorts with no discontinuations. Most adverse events were mild and not attributed to the study drug. Dose-related reductions in HBV DNA were observed, the largest of which was in the NVR 3-778 and pegylated interferon combination (1.97 log IU/mL). Using NVR 3-778 alone, the HBV DNA reduction was 1.72 log10 in the 600 mg BD group, and in the pegylated interferon alone group the HBV DNA reduction was 1.06 log10. Study results also indicated early reductions in levels of HBeAg (a sign that the virus is actively replicating in the body and that the infection is worse) across all groups, which were greatest in the NVR 3-778 group.

"The results from this study are certainly interesting and promising for the treatment of patients with Hepatitis B,'" said Professor Frank Tacke, EASL Governing Board member. "The medical community is always on the look-out for treatments which can cure this condition, as opposed to simply suppressing the replication of the virus. More research is needed to confirm whether NVR 3-778 could really change the treatment paradigm."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)