Many people with advanced kidney cancer might not need to have their kidneys removed during treatment, something that until now has been standard practice.

Patients who only received a targeted drug for their kidney cancer survived just as well as those who had their cancerous organ removed before drug therapy, according to a new clinical trial.

"We believe this one study will change it so that patients won't get nephrectomies [kidney removal surgery]," said Dr. Bruce Johnson, chief clinical research officer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston. "If anything, it looks like it's a little bit better if you don't take it out. We think this single study will change what people do."

For about two decades, kidney removal followed by drug therapy has been the standard of care for people with advanced kidney cancer, said Johnson, who is also president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

"One of the things that's been odd about kidney cancer is even if you have metastatic disease, where it started in your kidney and spread through your body, there was evidence patients lived longer if you took out their kidney," Johnson said.

Cases where the cancer has spread account for about 20 percent of all kidney cancers worldwide, said study lead researcher Dr. Arnaud Mejean, a urologist with the Georges-Pompidou European Hospital at Paris Descartes University, in France.

But in the intervening years, a number of targeted therapies have been developed that attack the ability of kidney cancer to grow and spread, the researchers added.

Mejean and his colleagues set out to test whether these new targeted drugs are so powerful that they've removed the need for painful, body-wracking kidney removal surgery.

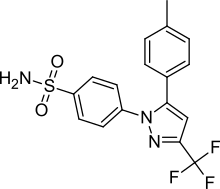

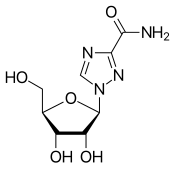

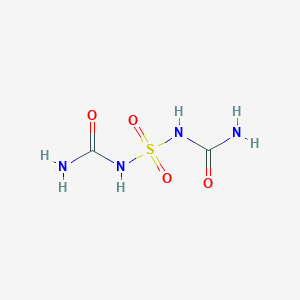

The clinical trial enrolled 450 patients with metastatic kidney cancer, and assigned them to either take the targeted drug sunitinib (Sutent) or have their kidney removed and then take sunitinib.

Sunitinib attacks blood vessel growth that allows cancer to spread throughout the body, and it also blocks other means by which kidney cancer can grow, according to the American Cancer Society.

The patients were followed for about 51 months, and during that time the researchers found that survival was not worse for patients who just took sunitinib.

Overall, survival was 18.4 months without surgery versus 13.9 months with surgery. Similar survival rates also were found in people with an intermediate or poor prognosis.

The two patient groups had a similar rate of tumor shrinkage (just over 27 percent for surgery and 29 percent for sunitinib alone), the findings showed. In addition, average time until cancer progressed was slightly longer for patients who received sunitinib alone compared with those who also had surgery (8.3 months versus 7.2 months).

People who undergo kidney removal must heal before they can start targeted cancer drugs, often losing weeks they don't have to spare, the researchers noted. In some cases, the cancer spreads so quickly during this delay that there's no time to start the drug therapy.

However, the study authors said kidney removal is still the gold standard for people who do not need targeted drug therapy, such as those whose cancer has only spread to one other organ.

Despite these findings, it's not clear that all kidney removal surgeries will end for people with advanced kidney cancer, said Dr. Daniel Cho. He's a medical oncologist at NYU Langone Health's Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City, and was not involved with the study.

"I don't think it should be across the board a standard of care yet," Cho said.

This approach may work for patients receiving targeted drug therapies, but may not be as effective in patients who are undergoing immunotherapy -- taking drugs to boost their immune system's ability to detect and kill cancer cells, he said.

Some people believe that large kidney tumors actually suppress the immune system and are not very responsive to immunotherapy drugs, Cho said. For the best results in these patients, kidney removal may be necessary.

"There's a certain rationale to remove the primary tumor if you're planning to give immunotherapy," Cho said. "The primary tumor may be creating a more immunosuppressive environment that makes the immune therapy less effective."

On the other hand, "there are those patients who are more likely to have rapidly growing disease, and therefore would more likely benefit from immediate systemic therapy," Cho added. "I really believe we have to be thoughtful about it."