In continuation of my update on

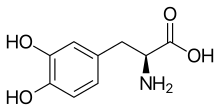

L-Dopa

The most potent drug available for Parkinson's disease, levodopa, treats symptoms of the disease but does nothing to either ease or increase its still-mysterious underlying causes, a new clinical trial has concluded.

Doctors often delay prescribing levodopa, or L-dopa, to Parkinson's patients for fear that the drug might have toxic effects that produce jerky involuntary body movements over time.

But patients started on L-dopa nearly a year earlier than a second group did not develop significantly different rates of involuntary movement, results from the new trial show.

"The current study bolsters our confidence that levodopa is safe even in early Parkinson's disease and that patients should not fear it," said Dr. Michael Okun. He's the national medical director of the Parkinson's Foundation and chairman of neurology at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

There's disappointment here as well. While levodopa isn't toxic, it also doesn't appear to provide any protection against progression of Parkinson's in the brain, said Dr. Susan Bressman, co-director of the Mount Sinai Parkinson and Movement Disorders Center in New York City.

"The bottom line is they couldn't show neuroprotection," Bressman said. "Using this very normal dose we normally use, they couldn't show it slows the progression of the disease."

Parkinson's disease is a progressive nervous system disorder. One of its hallmarks is the loss of neurons that produce a brain chemical called dopamine. Low dopamine levels affect a person's control over their movements, causing tremors, rigid muscles and slowness.

Developed more than 50 years ago, L-dopa eases these muscular and movement symptoms. The brain synthesizes levodopa into dopamine and then puts the neurotransmitter to good use.

"Levodopa remains the most important and effective treatment for Parkinson's disease and its introduction has undoubtedly improved morbidity, mortality and quality of life," said Okun, who wasn't part of the trial.

But side effects in some patients cause concern that the drug might have a toxic effect on the brain, researchers noted.

A clinical trial 14 years ago that aimed to clear up the matter only muddied the waters, Bressman said.

The earlier trial found that people taking L-dopa showed improvement even after they stopped taking it, raising hopes that it might be somehow be stemming the progression of Parkinson's.

But brain scans of those patients showed some evidence that levodopa was causing potentially harmful changes to dopamine receptors in the brain, Bressman said.

"We couldn't really prove one way or the other if it's good or bad for the brain," Bressman said. "But the bottom line -- people need it. We don't have a better drug. It's the most potent drug for the symptoms, so you've got to use it, but you don't use a high dose."

The new clinical trial, led by Dr. Rob de Bie from the University of Amsterdam, hoped to clarify results of the older study.

A group of 445 early Parkinson's patients in the Netherlands were randomly assigned to either start levodopa therapy right away, or wait 40 weeks and then start taking the drug.

"The theory is if you get those extra 40 weeks of exposure to levodopa and it's neuroprotective, the earlier group will be in a better place and the late group will never catch up," Bressman said. "They'll always be a little worse because the first group got more of this neuroprotective effect."

But both groups wound up in the same place by week 80 of the trial, with essentially the same rate of disease progression, the Dutch researchers found. The drug didn't provide people in the earlier group any extra protection.

At the same time, neither group suffered greater rates of jerky movements or levodopa-related fluctuations in motor response, discounting concerns over toxic effects.

"Basically, it confirms what we currently do," said Bressman, co-author of an editorial accompanying the study. Both were published in the Jan. 24 issue of New England Journal of Medicine.

"Most people don't start levodopa at first diagnosis, when they have hardly any symptoms, because they don't need it. We don't think the drug is protecting the brain, so we don't start it right away, because it's not going to change what they're going to look like 10 years down the pike," she noted.

"But as soon as they do start to need it, we start it. We use it. And we're judicious in how we use it," Bressman continued.

Hopes for a drug that will directly treat or perhaps even cure Parkinson's now rest on research being done into suspected causes of the disease, she said.

Experts now think Parkinson's is a related group of diseases, each subtype potentially triggered by a different cause, Bressman said.

Drugs are being developed to target genes that have been implicated in Parkinson's for some patients. Future drugs might target inflammation in the brain or other potential causes.

"I think ultimately between the genetics and other biomarkers we find in the spinal fluid or in the blood, we're going to be able to group patients better and figure out the disease mechanisms," Bressman said.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L-DOPA