Antibiotic resistance is a growing public health problem across the globe, with many diseases becoming harder to treat. Now, a newly discovered antibiotic group shows promise in the fight against superbugs as it has a unique way of killing bacteria.

A team of scientists at McMaster University has found a new group of antibiotics that can fight infections in a new and unique way. These antibiotics fight infections in a way researchers have never seen before, according to the findings of the study described in the journal Nature.

'Holy grail' of antibiotics

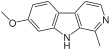

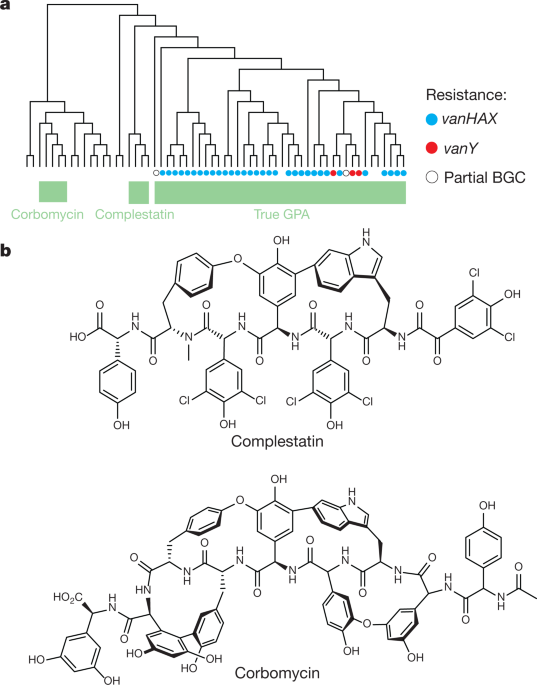

The newly found group of antibiotics, consisting of corbomycin and complestatin, can kill bacteria by blocking the function of the bacterial cell wall. These drugs come from a family of antibiotics known as glycopeptides, which are produced by soil bacteria.

The two antibiotics attack peptidoglycan, the main component of the bacterial cell wall that is vital to the growth and survival of almost all bacteria. They inhibit the action of autolysins, which are important for cell division and growth.

Other antibiotics, such as penicillin, work by preventing the bacteria from building its wall, which is the source of its strength. In killing the bacteria, removing its wall will make it vulnerable and easier to kill.

These new antibiotics work by doing the opposite. Instead of preventing building the wall, it halts the wall ll from being broken down. As a result, blocking the breakdown of the wall would make it impossible for them to divide and expand – just like being trapped in prison.

Unique bacteria killer

The two new antibiotics are known as glycopeptides. The team studied the genes of the group to see if they lack resistance mechanisms. The team believes that if the genes that made these drugs different, perhaps the way they kill will also be different.

In collaboration with scientists from the Université de Montréal, including Yves Brun, they found that the drugs act on the bacterial cell wall to prevent it from dividing and proliferating.

"Knowing the detailed structure at the atomic level of this connection between the surface layer and the surface of the cell offers enormous potential to then develop molecules that can target this attachment and make the cell more sensitive to antibacterials," Yves Brun, study co-author, said.

"Combined with the discovery of the new mode of action of two antibiotics, this development opens up prospects for weakening the action of bacteria and making them more vulnerable," he added.

The researchers believe the group of drugs is a promising clinical candidate in the hopes of stemming bacteria from becoming resistant to antibiotics.

Fight against antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest threats to global health, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Though it happens naturally, the misuse of antibiotics is hastening the process, making it easy to treat infections in the past harder to curb now.

Further, antibiotic resistance increase hospital stays and medical costs. For instance, diseases in the past that were responsive to certain antibiotics may become resistant and difficult to stem, such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, gonorrhea, and other infections. Now, as the diseases become stronger and more resilient, outbreaks may become inevitable, unless new drugs are discovered.

In the United States alone, at least 2.8 million people become infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year, while more than 35,000 people die.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-1990-9